Spanish, and English: Lenguas cambiantes y múltiples

October 27, 2013 § Leave a comment

I read a wonderful essay yesterday in El País (an international Spanish-language newspaper, headquartered in Spain). The sixth International Conference of the Spanish Language just concluded in Panama, a triennial meeting with the purpose of examining the state of the Spanish language. No equivalent of this group exists for English speakers, as far as I know: the closest cousin I can think of would be the hoopla that follows the publication of a new Associated Press Stylebook or the OED’s release of words added to the dictionary that year.

The main difference that strikes me between English- and Spanish-speaking word people is that Spanish-speakers aren’t quite the snobbish, stubborn nitpickers we are. Rather than shoving personal preferences about the serial comma or the right way to write the word “website” down one another’s throats, attendees and members of the Instituto Cervantes, which organizes the conference, seem to celebrate Spanish in all its difference and diversity.

Sergio Ramirez, a Nicaraguan writer who gave the CILE’s inaugural address, illuminates just this point. For much of its history, Spanish has been the language of poverty and oppression; of frontier-crossing and culture-blending. Of course the language spoken in Bogotá doesn’t sound like that spoken in Madrid. These differences are something worth celebrating, not stifling.

As writers, editors, scholars, and general English-language obsessives, I think there’s a lot we can learn from our Spanish-speaking counterparts. Here are translations of a few of my favorite passages of Ramirez’ essay, excerpted from his CILE speech.

Soy un escritor de una lengua vasta, cambiante y múltiple, sin fronteras ni compartimientos, que en lugar de recogerse sobre sí misma se expande cada día, haciéndose más rica en la medida en que camina territorios, emigra, muta, se viste y de desviste, se mezcla, gana lo que puede otros idiomas, se aposenta, se queda, reemprende viaje y sigue andando, lengua caminante, revoltosa y entrometida, sorpresiva, maleable. Puedo volar toda una noche, de Managua a Buenos Aires, o de la ciudad de México a Los Ángeles, y siempre me estarán oyendo en mi español centroamericano.

I am a writer of a language that is vast, changing, and numerous; without borders or boxes; that, rather than gathering up around itself, expands each day, making itself ever richer as it crosses territories, migrates, mutates, covers and uncovers itself, mixes, takes what it can from other languages, takes root and remains, then resumes the journey and continues walking; a moving tongue, rebellious and meddling, unexpected, malleable. I can fly through the night, from Managua to Buenos Aires, or from Mexico City to Los Angeles, and all along I will hear the Spanish of Central America.

Cuando en América hablamos acerca de la identidad compartida, nuestro punto de partida, y de referencia común, es la lengua. No somos una identidad étnica, no somos una multitud homogénea, no somos una raza, somos muchas razas. La diversidad es lo que hace la identidad. Tendremos identidad mientras la busquemos y queramos encontrarnos en el otro. Pero somos una lengua, que tampoco es homogénea. La lengua desde la que vengo, y hacia la que voy, y que mientras se halla en movimiento, me lleva consigo de uno a otro territorio, territorios reales o territorios verbales.

When in the Americas we talk of a shared identity, our point of departure, our shared reference, is language. We are not one ethnic identity, nor a homogenous multitude; we are not one race, we are many races. Diversity is what makes our identity. We gain identity as we search for it, and as we seek to find it in others. But we are a single language, which is not homogeneous either. The language from which I come, and toward which I go, and that is moving all the while, carries me with it from one land to another, lands both real and verbal.

Quienes la hablan y quienes la escriben son protagonistas de esa invasión verbal que cada vez más tendrá consecuencias culturales. Consecuencias de dos vías, por supuesto, porque cuando las aguas de un idioma entran en las de otro, se produce siempre un fenómeno de mutuo enriquecimiento.

La lengua que gana nuevos códigos cerca del lenguaje digital, de los nuevos paradigmas de la comunicación, de los libros electrónicos, de las infinitas bibliotecas virtuales que estuvieron desde antes en la imaginación de Borges, y que gana modernidad mientras se adentra en el siglo veintiuno.

El Gran Lengua seguirá siendo el vocero de la tribu. El que tiene el don de la palabra y representa así a los que no tienen voz. El que alza la voz, es él mismo la lengua, la encarna, y se encarna en ella. Guarda y publica la memoria de las ocurrencias del pasado, inventa, imagina, interpreta, recrea, explica, y seduce con las palabras.

¿A qué otra cosa mejor puede aspirar un escritor, sino a ser lengua de una tribu tan variada y tan vasta?

Those who speak and those who write are the protagonists of this verbal invasion of ever-greater cultural effects. Effects in both directions, of course; because when the waters of one language enter those of another, the result is always an enrichment of each.

A language that takes on the new terms of digital technology, of new communication paradigms, of e-books, of the infinite virtual libraries that before lived only in the imagination of Borges, and that gains modernity as it enters the twenty-first century.

The Great Language will remain the voice of the tribe. Those with the gift of words, therefore, represent those without a voice. He that raises his voice, is language himself; he brings it to life, and comes to life within it. He protects and spreads the memory of what has gone before, and invents, imagines, interprets, recreates, explains and seduces with his words.

What else could a writer hope for, than to be the language of a tribe so varied and vast?

19 Emotions For Which English Has No Words

May 15, 2013 § Leave a comment

I’ve long been interested in the limitations of language—and the loopholes offered by learning the words of another. Awesome infographic by Pei-Ying Lin via FastCompany (click to make it big).

Also, file under “why hadn’t this been invented yet”: The Emotionary. It’s a list of emotions for which English (until now) has no words. See vindexance (“the immediate desire to redeem oneself upon realizing what you should have said or done moments after it is too late”) and epiphannaise (“the moment one realizes aioli and mayonnaise are exactly the same thing”).

Users can submit new words for once-inexplicable feelings. Personally, I’m looking forward to the “words most felt” page (coming soon!).

Every language needs its, like, filler words – io9

April 22, 2013 § Leave a comment

We’ve always been advised to, like, avoid using “filler words.” Y’know, words like “um,” “I mean,” “well,” “uh,” and stuff?

Here’s an interesting—but not all that surprising—finding. These words actually do serve a purpose. In a research study, participants were quicker to respond to commands from a computer that did use filler words than from one that didn’t.

To listeners, “uh” indicates that something new, which requires more mental processing on the part of the speaker, is about to be introduced. This helped the study participants put themselves in the right mindset of choosing from the as-yet unfamiliar objects.

They might not be the most elegant utterances to hear, but in some small way, these words carry meaning—and they aid our understanding. I’ve noticed Spanish and English both have their own sets of filler words—and according to the article, so does every other language.

I dunno, I guess that means filler words, like, aren’t so bad after all.

The Treachery of Translators – NYTimes.com

February 4, 2013 § Leave a comment

The Treachery of Translators – NYTimes.com.

Posting this in celebration of my first-ever English-Spanish translation project, which I’m SUPER excited about. True translation is (almost always) impossible. But it doesn’t stop us from trying.

“I had this realization that every individual language does at least one thing better than every other language.”

December 22, 2012 § Leave a comment

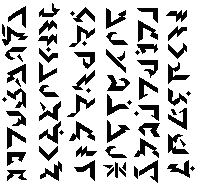

Image via Wikimedia Commons. By the way, it’s Ithkuil for “As our vehicle leaves the ground and plunges over the edge of the cliff toward the valley floor, I ponder whether it is possible that one might allege I am guilty of an act of moral failure, having failed to maintain a proper course along the roadway.”

If I weren’t a writer, I would definitely be a linguist. And as someone who used to make up my own languages as a kid (and then journal in them—no joke), I love reading about stuff like this. Great (but long) read by Joshua Foer, who tells the story of Ithkuil, one of the world’s most “efficient” languages—and its enigmatic creator.